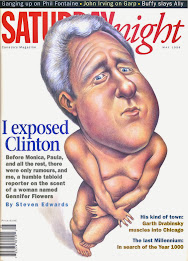

BILL CLINTON, GENNIFER FLOWERS, AND ME

Like the sensational political novel from which it is adapted, the movie Primary Colors is a brazen pastiche of fact and innuendo. Each shift of John Travolta's bulked-up frame reminds us of just one man, or more precisely, one president. Each behind-the-scenes machination is a candid camera's peek at the events that defined Bill Clinton's first run at the White House, or so the nudging and winking of the movie's promoters would have us believe. But while the movie may approximate the reality of the campaign -- I really can't tell you, I wasn't in that particular war room -- its simulation of how a weekly supermarket tabloid breaks the story of Governor Jack Stanton's affair with a blonde bimbo is pure Hollywood.

In the book and the movie, the lady in red is one Cashmere McLeod, hairdresser to the governor's wife. Somehow -- we're never told just how -- she hooks up with a tab called the National Flash and sells her tale of an affair with the presidential contender. And that's all there is to it. There's no indication that the tabloid's reporters did any legwork to obtain the story. Hard cash is apparently the only investigative tool available to the National Flash.

In real life, a tabloid, the Star, was indeed the first news organization to tell the world about Clinton's womanizing. But the reality is that its four-page report, dated January 28, 1992, under a headline trumpeting that Clinton, a Democratic front-runner, had cheated with Miss America and four other beauties, cost no more than the hotel and travel expenses of the journalists involved. Compiling the facts for the story did require serious investigation conducted at high speed, which may be what incensed the mainstream media so much. The Star entered their territory (the political arena) and beat them fair and square. True, money was subsequently handed over for a world-exclusive interview with one of the damsels in question. But the steps taken were far more sophisticated than hoisting a chequebook to the top of a flagpole and waiting for some cash-hungry source to climb up.

How do I know? My name was on the original story when it broke in the Star. I was also the first reporter to get to Gennifer Flowers.

I had been with the paper for a little more than a year when I was sent to Arkansas to try to pry open the Pandora's box of Clinton's sexual past. I had signed on after returning to Canada from Europe in 1990 and finding newspaper jobs here difficult to land owing to hiring freezes. Having grown up in Britain, I was familiar with a wide range of tabloids and, as a young journalist in western Canada in the first half of the 1980s, had tried to emulate their vivacity. What impressed me about the tabs both then and now is that their news agenda is not driven by press conferences and news releases, but by the demands of their readers. Consequently, tab reporters learn to be relentless in pursuing what sells and less pompous than the mainstream media on this continent when it comes to defining what's news.

That there might be bones rattling in Clinton's closet had been obliquely suggested in a Wall Street Journal profile of the candidate. To counter rumours of marital infidelities, the newspaper said, Clinton had taken the "unusual step of having his wife accompany him to a breakfast with political reporters in Washington." That was all the bait the Star's editors in Tarrytown, New York, needed to point their collective dorsal fin in the direction of Little Rock. The story was outside the usual sphere of tabloid interest, which is Hollywood, but it appeared to involve something the tabloids love to expose: phoneyness on the part of a celebrity (albeit a political one). Clinton was striving to maximize the puritan vote by presenting himself as a dedicated family man. We would endeavour to show that he was dedicated to his alleged mistresses. No sooner had the Star's editors wrapped up their 9 a.m. story meeting than Marion Collins, a veteran reporter with a trademark Scottish brogue, was asked to see what she could dig up.

After a morning of intensive telephoning, Collins learned that a disaffected Clinton associate, Larry Nichols, had reacted to his firing as marketing director of the Arkansas Development Finance Authority (ADFA) by launching a lawsuit in which he named five women he said the Arkansas governor had slept with while married to Hillary Rodham Clinton. The official reason for the firing was that Nichols had made unauthorized long-distance phone calls; he claimed it was because he'd discovered that Wooten Epes, the president of the ADFA, ran a slush fund to bankroll Clinton's bid to enter the White House. Apparently, the lawsuit had been around for some time, but the sleepy local press had never reported extensively on its contents. They'd had the legal right to do so, even if they'd lacked irrefutable proof that the affairs had taken place. Something known as "reporter's privilege" allows the media to publicize court proceedings without fear of a libel action as long as the news reports are fair, balanced, an impartial.

To obtain a copy of the lawsuit, Collins asked Chris Bell, the Star's Alabama-based freelancer and a quintessential Southern gentleman, to fly to Little Rock and visit the courthouse where it was filed. He was on the next plane.

By ten the following morning, the Star's editors were poring over some thirty pages of Bell's FedExed photocopy of the lawsuit. Within an hour, they had decided to send me to Arkansas to see what more could be uncovered.

Larry Nichols lived in a small town called Conway about a twenty-five-minute drive from Little Rock. His telephone number was listed in my hotel-room directory, but I followed my golden rule of trying to make first contact in person if the story is controversial. It's too easy for people who don't want to talk to you to just hang up the phone, then avoid you when you try to reach them in some other way. There was no answer when I knocked on the door of Nichols's one-storey, middle-class home. The garage door was wide open and there was no car to be seen. After waiting for about an hour, I left a note asking that he call me.

I had no sooner arrived back at my hotel than the phone rang. "Hey, Steve," a voice chirped in a tone you'd expect from a pal you've known for years. "Larry here. I hear you're lookin' for me." Before I had a chance to speak, Nichols asked me when and where I'd like to meet him. "You pick a spot, and how about now?" I said. Nichols gave me directions to a family restaurant not far from his home. The restaurant had an all-you-can-eat salad bar and Nichols had an all-you-can-listen-to story.

While working for the ADFA, he said, he'd raised money for the Contras -- Nicaragua's anti-Communist resistance. That, he claimed, was the reason for the contentious phone calls, and he insisted they had all been authorized. I had come for other information, however. I pressed him about the women he'd named in his lawsuit. Nichols obliged; he was eager to squeal in whatever pitch retained my attention.

There are three possible motives driving a person to inform on another: civic duty, money, and revenge. Journalists prefer sources who open up out of a sense of civic duty. Such sources are less likely to exaggerate or twist the story. Unfortunately, Nichols didn't seem the civic-duty type. As for money, he mentioned it only once, when he handed me the restaurant bill for $5.86 and drawled: "Y'all gonna pay this?" He was, of course, seeking $3-million (U.S.) plus change in his suit against Clinton, Epes, and the ADFA, but I think even he knew that his court action was unlikely to go much farther than the editorial offices of interested media. That left revenge. Nichols was certainly hopping mad about his dismissal. That didn't necessarily mean that his accusations were false. Indeed, if they were false, why hadn't Clinton countersued? Was he afraid of perjuring himself in court?

Of the five women named in the lawsuit, Nichols told me he had tapes of two of them admitting they'd experienced close encounters of the Clinton kind. Nichols would neither release the tapes to me (assuming they even existed) nor identify which two women were on them. Fortunately, we didn't need the tapes to break the story.

I spent the days following my meeting with Nichols gathering as much information as possible on the women. I spoke to anyone who had been associated with them: landlords, work associates, family, neighbours. In the meantime, our photo desk gathered pictures. This was made easier by the fact that, in one way or another, all five had been in the public eye. Two were beauty queens, another was a TV journalist, one was a Clinton press aide, and one -- as all America was soon to learn -- was a cabaret singer named Gennifer Flowers.

As my notebook swelled, it became clear I should concentrate on the beauty queens and Flowers as the most likely candidates for tell-all interviews. I supposed the TV reporter would not risk the ridicule and raillery of her journalistic peers by appearing in the infamous tabloid press. What's more, she was all the way over in Mississippi. I could go there only if I were sure she'd give me an exclusive interview. She went to the top of my to-telephone list. (When I called, she denied having had sexual relations with Clinton, and I pursued her no further.) As for the press aide, she was still on Clinton's payroll, so it seemed very unlikely she would talk. When Collins phoned her from Tarrytown, she was apparently vehement in accusing Nichols of being a liar. Nichols himself later said he had been mistaken about her.

The remaining three women had dreams of show-business stardom in one form or another. It was possible that they'd dump on Clinton in the hope that getting their glossies in the Star would set their telephones ringing. One of the beauty queens was the former Miss America, Liz Ward, who had since changed her surname to Ward Gracen. She lived in California, so meeting her would be the job of a staff member in the Star's Beverly Hills bureau. The other was Lencola Sullivan, who, in 1981, had become the first African-American to be crowned Miss Arkansas. She also lived out of town, but I learned she was in Little Rock to address a meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). I put her at the top of my "hit list" alongside Gennifer Flowers, whose Little Rock address I had yet to find.

The remaining three women had dreams of show-business stardom in one form or another. It was possible that they'd dump on Clinton in the hope that getting their glossies in the Star would set their telephones ringing. One of the beauty queens was the former Miss America, Liz Ward, who had since changed her surname to Ward Gracen. She lived in California, so meeting her would be the job of a staff member in the Star's Beverly Hills bureau. The other was Lencola Sullivan, who, in 1981, had become the first African-American to be crowned Miss Arkansas. She also lived out of town, but I learned she was in Little Rock to address a meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). I put her at the top of my "hit list" alongside Gennifer Flowers, whose Little Rock address I had yet to find. I visited Lencola Sullivan's family home in the hope that she was staying there while in the state. I spoke only to a family member who agreed to pass on a note from me that explained why I wanted to talk to her. To give her an extra push, I attended the NAACP meeting.

I arrived early and was particularly pleased to see that another celebrity besides Sullivan would be in attendance -- Daisy Bates. Mrs. Bates, now in her late seventies, was at the forefront of the tumultuous events surrounding the racial integration of Little Rock's Central High School during 1957-58. Her memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock, was for sale at the meeting. She was just signing "To Steve with love ...." in my copy when Lencola Sullivan arrived.

Her speech was about black women and success. I approached her as soon as it was over. To say that I was conspicuous would be an understatement; mine was the only white face among the crowd of people trying to shake her hand. I told Sullivan why I was there, and asked when and where it would be convenient to contact her. "I'm busy right now," she said with a weak smile. It would have been no use pressing the matter in such a throng. I handed her a card on which I had written my name and the number of my hotel. I asked her to please call, that I simply wanted to get to the truth. She smiled again and took the card. I think she was relieved that I had not made a scene. She never did call, and I had too many other avenues to follow to pursue her any further.

One of those avenues, I hoped, would lead me to Flowers. There was no listing for her in the phone book, nor in those cross-referenced city directories at the library that debt collectors like to use. By calling a place where Nichols told me she'd appeared as a singer, I learned the name of a booking agent who'd once landed her a few gigs, Jim Porter. I phoned Porter to ask if he knew where Flowers was now. He laughed and said a reporter from The Washington Post had just been on the phone to ask him the same thing. Aha! The Post was also on her trail... and ahead of me. There was no time to waste.

Porter told me that he hadn't spoken to Flowers in ages. He explained how he'd got her a job singing back-up with Roy Clark, a country-and-western artist. But that was ten years earlier. He had no idea where she was now -- except that she worked for the state government.

Trying to reach Flowers through the personnel department of the government was a no-no; I'd have had to leave a message identifying myself. I suppose I could have claimed to be an old friend or a relative. But my American accent is about as believable as Clinton's subsequent "I didn't inhale" claim.

Hoping that Flowers might still be singing in some bar or other, I did the rounds of Little Rock's nightclubs. In each one, I asked the staff and the singers if they'd heard of Gennifer Flowers. None had. It seemed that Gennifer's show-girl days were mere memory. She was now more of a no-show girl.

I needed a break, and one arrived on a Saturday night at a popular spot called Landry's Cajun Wharf. I'd just finished eating with Chris Bell, the Alabama freelancer, and Steve Connolly, a Boston-based freelance photographer the Star often uses. I had done my duty by asking the singer of the band there if she'd heard of Gennifer Flowers. Bell had done his by putting the same question to the shoe-shine man situated between the Gents and the Ladies. We both ended up with answers in the negative, but Bell at least walked away with a spit and polish.

We met up in the bar and talked about driving over to a former Clinton hangout to see if we could pick up any new leads. It seemed impossible that in such a small city we could find no-one who knew the current whereabouts of a woman who had supposedly been something of a local celebrity. To make light of our failure, Connolly turned to a young woman standing behind us and said: "Do you know Gennifer Flowers?" And bingo! The woman -- a certain Miss Tammy Brooks -- said yes. The pair had met through a security firm where Brooks had worked.

Brooks asked us why we were seeking Flowers. We told her we were from the Star, an admission that always provokes a reaction. People tend to start asking you for the most intimate details of the lives of their favourite Hollywood actors, or berate the magazine as a rag they wouldn't even use to line the bottom of their bird cage. At that moment, the woman standing next to Brooks -- her mother -- piped up. "They're having you on" she said. Then she turned to us and said, "We're just leaving." That prompted me to order refills for our newly discovered fountains of knowledge. We explained that talking to Flowers was all that stood between us and a sensational story. Though her mother remained reticent, this seemed to intrigue Brooks. She was able to provide Flowers's number by calling a friend that she and the singer had in common. "Try to get her address, too," I said. Flowers was the only one of the five we didn't have a photo of yet. Knowing where she lived would take care of that.

Brooks made the call, but could coax only Flowers's number from her friend. Within minutes, I was listening to the phone ringing at Flowers's home. I would say nothing that could possibly prompt Flowers to hang up. My mission was to get her to meet with me the next morning.

"Who gave you my number?" were her first words after I'd identified myself. I was tempted to say: "A guy named Bill." Instead, I said that I was always discreet about the identity of my sources. For that very reason, I continued, she could trust me. I explained that I wanted to talk to her at length about the Nichols lawsuit and the allegations it contained involving her. She was very reserved, but I told her that she should at least meet with me to hear how she, too, could benefit from speaking out. "You've got nothing to lose by simply listening to me," I said. After hesitating for a few moments, she agreed to have breakfast with me on the condition that I turn up alone and that no pictures be taken. "Oh certainly," I said, thankful I didn't have to lie to her face.

Flowers suggested we get together at 10:30 a.m. in the breakfast room of the Holiday Inn on the edge of town. She gave me directions from my hotel, then told me how I'd recognize her: "I have blonde hair," she said, "and I'll be wearing a black leather coat." After a pause, she revised her description: "I have frosted blonde hair."

|

| Exclusive: Gennifer and Me |

Next morning, Steve Connolly, Chris Bell, and I arrived at the Holiday Inn well in advance of 10:30 so we could plan how we'd photograph Flowers without her knowing. Connolly said he'd plant himself on the mezzanine overlooking the breakfast room, and pointed to a table that would give him a direct view of our target through his telephoto lens. "Make sure she is facing that way," he said, pointing at the mezzanine. Then he and Bell disappeared. Flowers arrived, accompanied by a woman whom she described as her publicity agent, but who was probably just a friend, given that Flowers didn't seem to be doing too much singing any more. I shook hands with the two women and quickly sat in a chair next to the seat I wanted Flowers to take. She sat exactly where I had hoped. I then launched my bid to win her over for a full interview.

I began by emphasizing that Clinton's handlers presented their candidate as a caring family man -- for example, he supposedly checked his daughter Chelsea's homework by fax when he was campaigning -- and added that the public might appreciate knowing the truth. Flowers strained to choose words that admitted to nothing. She said she had a story to tell, but added: "I'm afraid of the repercussions if I talk about it." She said that if she did decide to speak out, she would tell her story to a reputable newspaper. She made a special point of singling out The Washington Post as her publication of preference. Thank goodness, I thought, that the Post reporter who'd been on her trail had not reached her first.

To counter her apparent disdain for tabloids, I spoke of the Star's virtues, emphasizing that the magazine had never indulged in wacky stories about two-headed calves or Elvis sightings, and so on. "It's simply a publication that is full of behind-the-scenes stories about Hollywood celebrities," I said, adding that she, as an aspiring star, could only see her singing career boosted if she appeared alongside an array of show-biz greats. Flowers's expression remained serious. If nothing else, she was paying close attention to what I was saying.

I next asked her if she had evidence to back up the story she planned to tell. She told me she had tapes of numerous telephone conversations with Clinton which would be sufficiently revelatory. "Why did you tape him?" I asked. She said: "For my own protection." She added that she'd made the tapes as "insurance" in case she had to use them one day.

I knew we had our breaking story, but I was determined not to let the opportunity for a full interview with Flowers slip through my fingers. I had been authorized to mention a five-digit figure, and did so. I told her that the Star might like to buy the exclusive rights to her story.

Buying the "big story" is widely practised in Britain, but frowned upon by North America's mainstream media, who consider it somehow immoral. Yet that doesn't stop them from reporting extensively on scandals that were exposed thanks to a tabloid payoff. If the payoff is immoral, then benefiting from the payoff farther down the line is also immoral. The fact is that neither the initial "bought" story nor the spin-offs are inconsistent with ethically sound journalism. All media have a right to investigate matters of public interest using any legal means available. If the protagonist of a major story requires money to be coaxed into the open, so be it. The person's words, once made public, will be subject to just as much scrutiny for libel or slander as words emanating from unpaid sources -- if not more.

Flowers maintained her impassive look as I spoke of the possibility of a fee. I made it clear that money would be paid only if her story had substance and if the information she gave was consistent with the information that we, at the Star, had already gathered. More importantly, I said, the tapes had to clearly indicate that a relationship had taken place between her and Clinton. Flowers assured me they did.

Buying a story is like buying a car: you have to kick the tires first to make sure that what you are paying for is sound. Kicking the tires of a story involves hearing it in its entirety before any contract is signed. Not surprisingly, sources are reluctant to bare all; the magazine, they fear, might simply make off with their words and pay nothing. The compromise is an interim contract whereby the source agrees to tell all while the magazine agrees to print nothing until a final fee has been negotiated. I explained this to Flowers and said I could have examples of an interim contract and a final contract faxed to me from New York for her to look over. Flowers said she did want to see copies of the agreements, so I excused myself and called the Star's news editor, Dick Belsky, from a phone in the foyer.

Belsky said he'd fax a signed interim agreement aimed at assuring Flowers that any material she discussed with me would "not be published until a fee is negotiated with her," as well as a blank of a final contract. He also said that the Star's editor, Dick Kaplan, wanted to speak with Flowers after she had reviewed the agreements, to reassure her that she would be doing the right thing in dealing with us.

On my way back to the breakfast room, I glanced up to eye Connolly and Bell on the mezzanine. It was a sight that would have made any self-respecting sleuth smile. Bell was standing upright with a copy of The New York Times opened wide in his outstretched hands. Connolly, meanwhile, was crouched behind the newspaper, his lens pointed at Flowers. As Bell drew his hands together to turn the newspaper's pages, Connolly snapped several shots of his target. After a second or two, Bell opened his arms and hid Connolly behind the day's headlines.

After reclaiming my seat, I told Flowers she could pick up a saffron envelope containing copies of the agreement from my hotel at 1 p.m. I'd have been quite happy to hand her the copies personally, but she preferred not to be seen talking to me in a place where I was known to be a reporter. As it turned out, it's possible the Clinton campaign already knew we were in touch with Flowers. In a special election issue, Newsweek later reported: "[A] woman... phoned the campaign to report that two men with British accents had approached her looking for Flowers. They said they worked for the Star, she gave them Flowers's number." No doubt Connolly's New England accent had been mistaken for a British one.

Connolly rubbed his hands together when I told him Flowers would be dropping by our hotel at one. He would get another shot at photographing her. In preparation, he parked his Chrysler Imperial just to the right of the hotel's front door at around 12:30. With any luck, he surmised, Flowers would park right behind him. Connolly knelt on the back seat of his car, camera in hand, and waited. Flowers did as Connolly had hoped. The Star ended up using one of these snaps to accompany the breaking story.

I also snapped Flowers from my hotel-room window. It was the last time I saw her in person. That afternoon, Flowers found a lawyer. For his part, Kaplan proposed that the Star fly her to New York. This had two advantages: she would be insulated from other media, and the terms of the interview could also be more thoroughly negotiated at head office. The final fee reached six figures -- by far the most the Star had ever paid for an interview. Flowers, I heard, also demanded dresses and even collagen lip injections.

She and Marion Collins parleyed for two or three days in a suite in the Westchester Marriott hotel, just a parking lot away from the Star's head office. As the interview progressed, the initial story containing the stealthily taken photo of Flowers hit the streets. Now under contract, Flowers did not complain about the snap.

Part of her whistle-blowing involved a claim that Clinton had pulled strings to get her a state job as an administrative assistant at $17,520 a year. A grievance had been filed by the woman who'd been overlooked in favour of Flowers, so I dug around, obtained a copy, and sent in a report.

In Little Rock, the issue containing the breaking story sold out within hours. One of the copies was grabbed by a Clinton aide whose phone number -- to this day I don't know how -- ended up in Connolly's message box at our hotel. The aide, who praised our story for its accuracy, turned out to be so closely linked with Clinton that I pressed him to meet with me. He directed me to the underground parking lot of the Best Western Inn Towne in the southwest of the city. As it happened, the meeting place was not far from the Quapaw Tower condominiums, where Flowers had once lived. Just days earlier I had visited there to interview the manager, John Kauffman, who had told me of Clinton's frequent appearances up until the time Flowers moved out.

As I drew into the parking lot, two men guided me to a particular spot. I confess I was a little nervous as I got out of the car and was duly patted down. "We wanted to check you for wires," the men said. The pair then led me to the hotel's lounge where one of them identified himself as the aide. He introduced the other as a close friend whom, I presumed, he'd brought along for moral support.

The information the aide gave me was so strong that it might have toppled Clinton had we published it on the heels of the Flowers stories. But even the offer of a fee totalling a year's salary failed to coax him into allowing his identity to be published alongside his story. The Star's editors rightly felt that a "source-said" story -- no matter what the content -- could not possibly be used to follow Flowers's blockbuster admissions. "We'd be opening ourselves to accusations of fabrication," said Belsky. (In recent months, the aide was called to testify in the Paula Jones sexual-harassment case. But his deposition is likely to forever remain secret now that a federal judge has thrown out that particular lawsuit.)

My final meeting with the aide was as melodramatic as the first: two cars, one mine, one his, were parked on opposite sides of the road in torrential rain in front of an old greystone church. The headlights of his vehicle blinked to signal that I should make a mad dash through the downpour for his car. I told him one last time that we could run his story only if he agreed to let us use his name. He regretfully declined.

In between dealings with the Clinton aide, I came across a friend of Ward Gracen's who told me what she knew of the former Miss America's sexual encounter with Clinton in 1983. "She left a party with [Clinton]" said the friend. "They did it once. She was star-struck. Later, she thought she had made a mistake. She hadn't done it with malice in mind. She was just a young kid at the time. He was the governor. She felt it was his place to be restrained." Armed with this information, I tried to contact Ward Gracen in California. Her lawyer called me back, and I proposed that his client come on board to tell her story in her own words in the Star.

But then Ward Gracen witnessed the reception Flowers received at the Star's televised press conference at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York. Among the questions fired at her were two from "Stuttering John" Melendez, of the Howard Stern show, who specializes in asking impertinent questions of people in the news. Stuttering John asked Flowers whether Clinton had worn a condom and whether she planned on sleeping with any more presidential candidates. Flowers declined to answer either question. Ward Gracen said she would never subject herself to a similar "humiliation." Not until just a few weeks ago did she finally make her tryst with Clinton public. She said she came forward to rebut charges in the Paula Jones suit that Clinton had sexually assaulted her. Echoing what I had been told many years earlier, she told New York's Daily News that her sexual encounter with Clinton had been a "very bad error in judgment."

By now, the Clinton campaign was more eager than ever to contain any further stories about their candidate's sexual past. Still outstanding from the former Clinton associate Larry Nichols were the tapes he claimed to have, containing, he'd revealed in the interim, admissions by Sullivan and Ward Gracen that they'd each had sex with the Arkansas governor. I was overjoyed when Nichols finally agreed to give me the tapes. We set a time and a place. But when Steve Connolly and I turned up, Nichols bowed his head and said: "I'm sorry. My wife has threatened to divorce me if I take this any further, I've got to bail out now. I don't want to lose my family and kids." He later dropped his entire lawsuit.

The tapes were the last hope of coming up with a quick, but powerful, follow-up to the Flowers interview. Many reporters were beginning to turn their attention to a rumour that Clinton had evaded the draft. This wasn't a salacious enough story for Star readers' tastes, and I did not investigate the allegation with any zeal. That story eventually broke in The Wall Street Journal.

The Star gained worldwide publicity from the Clinton stories. The magazine also expected substantially increased sales, but though circulation figures for the three issues were up, they were nevertheless disappointing. This and the lack of a juicy, on-the-record blockbuster to follow the Flowers interview led the Star's editors to conclude we had done our duty in Arkansas and should pull out.

As a reward for my efforts, I was given a week's all-expenses-paid vacation anywhere in North America. I flew to Washington, D.C., not to continue with the Clinton story, but simply to visit the museums there. My vacation didn't last: three days after I checked into my hotel, Dick Belsky called to assign me to a new story that was "just a short drive away," in Virginia Beach.

Clinton, as we know, went on to become President. Flowers stripped for Penthouse and made a bundle. Marion Collins was promoted to the post of deputy news editor and got a big pay raise. I, meanwhile, quit the Star to become a poverty-stricken student reading economics and history in French at Université Laval in Quebec City. It was just something that took my fancy, okay? I'm back working as a journalist now, and taking solace in Clinton's reported admission, in his deposition in the Paula Jones case, that he did have a sexual relationship with Gennifer Flowers. And what do all the mainstream media who denounced our stories as "bad journalism" say to that? Now, if only all those Elvis sightings were true.

PHOTO (COLOR): LARRY NICHOLS

No comments:

Post a Comment